Is It Time to Get Moving (here or there)?

Many of you snowbirds are starting to return to the northern reaches of our United States. Traveling to warmer climates for the winter is a tradition for many families, as is moving to no-tax or lower-tax state upon retirement. Increasing interest in changing domicile—the location of a person’s true, fixed, principal, and permanent home—to select the best state for tax purposes is becoming more abundant.

Re-domiciling has become even more frequent during recent times as remote workers have found they can work from anywhere and as the “van- or RV-lifestyle” continues to trend.

We are often asked to give advice as to whether one should change domicile. Most often, people are thinking about the tax considerations; but there are so many non-tax considerations such as cost of living, being nearer to loved ones, and other lifestyle elements to weigh.

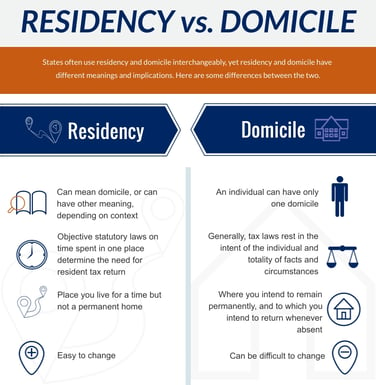

Residency Vs. Domicile

States often use residency and domicile interchangeably, yet residency and domicile have different meanings and implications.

Here is some context to determine the interpretation of residency and domicile:

- Most states with an income tax declare that domiciles are residents.

- An individual can have only one domicile.

- Residency can mean domicile, or can have another meaning, depending on the context.

- Income tax laws, estate tax laws, sales and use tax laws, property tax laws, and other jurisdictional laws may have differently worded definitions; but generally, domicile rests in the totality of the facts and circumstances and the intent of the individual.

- In the end, your domicile is where you intend to remain permanently and indefinitely and to which, whenever absent, you intend to return.

Domicile Definitions

Because of the subjectivity and fact-intensiveness of most domicile definitions, many states have also adopted a parallel statutory definition for residency for income tax purposes using more limited, objective criteria.

- Typically, the more objective-test statute will lay out criteria such as the number of days spent in a state, whether the individual maintains a home in the state, or some combination thereof.

- These statutory residency factors are most top of mind to individuals and why their first thoughts surround: “I can’t be considered domiciled in another state if I don’t spend six months and a day there.”

- While you want to avoid the objective statutory tests that could cause you to file a resident return in a particular state, you can only have one domicile and that will be your predominant residency.

- It is the subjective domicile rules that are the subject of dispute most often, but one reason to plan successfully for changing domicile is that the objective statutory residency laws can usually be easily avoided.

Changing Your Domicile State

Often, trying to un-domicile from one state is harder than setting up domicile in another state. Remember, states have revenue reasons to keep taxing you, and will often fight hard to keep taxing you even after you have left.

- Some states will presume you to remain a domicile until you meet certain conditions such as showing abandoning of your old domicile while acquiring a new domicile and showing physical presence in the new domicile. In other words, you are generally presumed to maintain your old domicile until a new one is established (through intention and actions).

- Your domicile should not change if you are only leaving a state for a brief period such as a vacation or to complete a particular transaction when you intend to return to your original domicile. Remember, for tax purposes the taxpayer generally has the burden of proof.

There can be some unique income tax filing considerations depending on the timing of a domicile change and the marital unit.

- For instance, if one spouse remains but the other spouse starts a new domicile you might both file as a resident of the new domicile, or one spouse could file as a resident of the new domicile while the other spouse files as a resident of the original domicile.

- The answer might rest in the tax benefit differences of filing jointly or separately (or if you are even allowed to do so) in the two states, or whether community property laws might dictate income and deduction reporting equally no matter how you file.

- Beware that if the separate domiciles of spouses continue too long, they might only qualify for $250,000 of the marital $500,000 capital gain exclusion on the sale of their home in the original domicile.

Income Tax Implications of Your Domicile Choice

Most states that have an income tax impose their tax on worldwide income. Further, even if you are filing as a resident of one state, you may have income sourced to another state where you will need to file non-resident tax returns even if you are not domiciled there.

- Selling property owned in another state, is one example of income that will be sourced to the nonresident state. Make no mistake that you will also pay tax on the sale in your state of residence. However, there will likely be some credit allowed for taxes paid to another state by your state of residency. The problem is your state of residency will likely limit that credit to the amount of tax paid to the resident state even if the nonresident state imposes a higher rate of tax.

- Another common reason people file nonresident returns is for pass-through business interests owned that operate outside the individual’s state of residency.

- Another thing to consider if you are torn between two states for domicile is that, besides potentially different income tax rates, some states might tax Social Security while others may not, and some might tax “retirement” income generally while others may not.

- In addition, some states, like Wisconsin, offer various reductions in capital gains income. States will also treat differently deferred compensation earned while domiciled in that state but paid once no longer domiciled there. These can be important considerations for executives and business owners with deferred compensation packages triggered by retirement.

Impact of the Homestead Exemption

The “homestead exemption” has two applications but both can be of importance when considering a change in domicile.

- First, as to property taxes – and don’t be disillusioned, property taxes not only vary greatly by locality, but by state. Generally, if you are domiciled in a state and pay property taxes on a home there, there will be some benefit (usually a partial exemption from the full assessed value or some form of property tax credit or associated income tax credit) called a homestead exemption or homestead credit.

- Mistakenly, trying to claim a homestead exemption in two states at the same time can be enough to blow your domicile claim in a particular state so renouncing your homestead designation in the state you are leaving (if continuing to maintain that home as a second residence) is important.

- Second, as to asset protection (namely bankruptcy creditor protection) states may either refer to the federal bankruptcy exemption allowance or provide a greater creditor-protection exemption.

Asset Protection Related to Marital/Spousal Property Rights

States may have different marital property laws related to spousal property rights during marriage, or in case of divorce. Some are state-specific, and some are more general based on if the state is considered a community property or common law property state.

- Generally, community property law states provide better spousal protections and better consequences at the death of one spouse for the surviving spouse.

- In community property states (also think marital property states like Wisconsin) the surviving spouse may inherit the property of the of the spouse with a stepped-up basis; and, in addition, their own property in which the deceased spouse had a marital interest will also be stepped up to the date of death value.

- This is why it is important when moving from one type of property law state to another that you keep records of the property owned when you move and the property later acquired as you might be able to afford yourselves of the most desired treatment if your records can help establish the character (community or not) of the property.

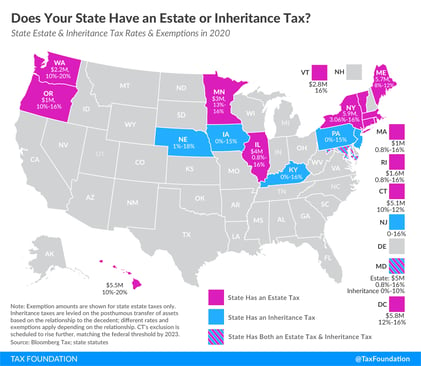

Impact of Estate Taxes

Besides income taxes/property taxes/asset protection, estate taxes can be a concern regarding domicile.

- Many states’ imposition of a death tax has evaporated since 2013 when the federal government eliminated the state death tax credit and, as a result, the states that used the state death tax credit as a measure for their state estate tax continue not to have a state estate tax.

- For the others that still have an estate tax, the tax can be significant and the savings often more than enough to fund setting up domicile in another state that doesn’t have an estate or inheritance tax.

- Estate laws of probate and inheritance, and power-of-attorney and trust laws (including how, at what rate, and when trusts/fiduciaries are taxed) are also different amongst states, so if you do move, make sure your documents are updated to comport with the state you move to.

- Generally, to avoid fiduciary state income taxes, you should consider changing your domicile to a state without fiduciary income taxes before your trust becomes irrevocable. Note that some states impose a fiduciary income tax on irrevocable trusts that are administered in that state.

Source: Tax Foundation

Source: Tax Foundation

Planning to Minimize State Death Tax is Simple.

Except for real property that is located in another state, you avoid a state estate or inheritance tax if you change your domicile to a state that does not impose a state death tax.

States that do impose an estate or inheritance tax will generally impose the tax upon the death of a person domiciled in that state or upon the death of a nonresident who owns real property located within that state. Even then, there might be planning opportunities to avoid or minimize the nonresident state death tax.

Many Choices Require Professional Assistance

There are, as pointed out at the beginning of this overview, a myriad of financial and nonfinancial considerations in picking a domicile.

Some we will not cover at length in this article but what could be considerations when modeling or decisioning your domicile move include:

- business taxes and “business climate”

- state sales tax rate differences

- cost of homeowner’s insurance differences (i.e., it costs more to insure in a state with regular dramatic weather like hurricanes in Florida),

- The real estate market differences will determine how much home you might afford, and weather itself can be a nonfinancial consideration for general lifestyle comfort or for climactic health reasons.

- Even buying and selling a home can be taxed differently amongst states with varied rates for the real estate transfer tax.

- Florida has a tax to pay when buying a home while using a mortgage called the mortgage stamp tax.

- Remember, states need to collect their revenue somewhere and if they have a low- or nonexistent-income tax, their other taxes are likely to be higher (i.e., Florida’s sales tax rate is one of the highest at 6% with other localities adding up to as much as another 2.5%).

There are many other nuances to consider and plan for that this article does not allow devotion to that should, nonetheless, be addressed when making a move.

If you are considering a change of domicile or have concerns about planning where your primary residence might be, consult with an advisor that can assist you that has the applicable expertise. Click the button below to contact an SVA professional today. We would be glad to help you.

© 2021 SVA Certified Public Accountants